A common error is to think of medical photography as just one new specialty among many, yet medical illustration is as old as medicine itself and the present is only a very short interval of time between the past and the future. [1]

This is an undeniable fact: paintings and illustrations are as old as mankind, while photography is far too young to be compared. The Camera Obscura (Latin for “vaulted chamber/room,” obscura for “dark”), which was invented only in 1457 and was mostly used by artists only as an aid to painting, was the forerunner of photography. As a result, the history of medical illustration cannot be overlooked, as it has evolved over a much longer period of time than the concept of medical photography.

The development of medical illustration is the result of medical philosophy, science, and spirituality over the past few hundred years. The first medical texts were descriptive but lacked visual images/illustrations. Texts were later accompanied by illustrations and became an integral part of medical education as it became clear that knowledge of the various systems of the human body was essential to medical practice. As medical science progressed, enabled by social, cultural, and technological changes, the types of illustrations evolved as well, from gross anatomy through dissections showing the various organ systems, histological preparations, and radiological and invisible light imaging, to the computerized digital image that is now available, allowing both two- and three-dimensional depictions to be transmitted electronically across the world. Medical illustration, in its infinite variety of techniques, has developed as a profession in its own right over the last century, though not in the Indian subcontinent.

The Ancient Evidence:

The primitive anatomy (of animals) has been represented in ancient cave paintings, primitively sculpted figures, and various forms of artistic expression throughout the ages. The earliest evidence of such an illustration dates back to 75,000 years ago, approximately 3000 BC. The most familiar subject was hunting, as illustrated by some unknown hunter-artists.

A hunter drew a crude illustration of an elephant on a prehistoric cave wall in southern Europe, and in its chest he delineated a vital spot, i.e., the heart. The unknown artist was aware that his arrows or spear worked better in that location. Similarly, there is a figure of a wounded lion with arrows stuck in its spine on the wall of a Babylonian temple. The creature’s posterior limbs are tiresome and stick-like; blood oozes from its wounds and nose, as one arrow appears to have entered the lung; and the forelimbs are in their final painful movements. Here, too, an unknown artist provided us with a visual representation of an animal in distress.

The Journey From Antiquity to Post-Renaissance:

Ancient Egypt: The Egyptians, though possessing some sound fundamentals in medicine and art, were really never able to achieve the freedom and natural beauty of their illustrations. Though, in the history of civilized mankind, Hellenistic anatomists like Herophilos (335–280 BC), deemed to be the first anatomist who started human dissection, of Alexandria in the 4th century BC studied anatomy through diagrams to illustrate the medical matters that they produced. [2]

Persian Civilization: Early Persian civilization produced crude biological drawings, which were made principally as ornaments or portraiture on vases, columns, and tablets.

The Eastern World: Eastern and Western medicine began with similar fusions of religion, spirituality, and science. Anatomists resorted to analogies of the universe to explain the body when superstitions surrounding death, and the fate of the soul prevented closer observation through dissection. By both moral and civil law, the Chinese were prevented from dissecting bodies and, consequently, from making anatomical drawings. (If you want to explore the divergence of Chinese and Western medical illustrations, here is the LINK to an outstanding article by Camillia Matuk).

Ancient Rome: The Romans made medical pictures that were mostly battle scenes or scenes of giving birth, but they tried to make the biological subject stand out. Based on what we know about how medical illustrations are used today, we could say that the Roman illustrations have a lot of visual subjects that don’t pay enough attention to key points and get lost in a large canvas.

Ancient Greece: Mysticism and superstition were used to describe Greek culture, and illustrations of medical science were not as accurate as those of science. However, an attempt was made to organize the diagram and give importance to a key subject. As time progressed, the Greek art pushed ahead of medicine by its own virtue. The human form was what attracted the artists, and their artistic creations differed from earlier non-scientific ones.They struggled meticulously to create the scientific form. In their mission to portray the exact human form, they were extremely conscious of body proportions. Undoubtedly, the Greeks contributed most to medical illustration because of the detail of their topography.

Other than Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BC), the father of Western Medicine, the Greek philosopher Aulus Cornelius Celsus of the 2nd century, contributed immensely to the development of medicine and wrote most notable books on anatomical, surgical, and pathological subjects, especially De Re Medecina. It is a presentation of therapeutic suggestions for common diseases and is illustrated with plates. Celsus’s academic successor, Galen of Pergamon (AD 129–c. 200/c. 216), a prominent Roman (of Greek ethnicity) philosopher, was arguably the most accomplished medical researcher of the Antiquity period. He contributed greatly to understanding numerous medical disciplines, including anatomy, physiology, pathology, pharmacology, and neurology, based on his anatomical observations on animal dissections, but mostly in a descriptive way.

Medieval Europe: After the decline of the Roman Empire, with the advent of Christianity and subsequently the Church’s dominance in medical research based on the stress on the soul rather than the body, medical studies in Europe were still to be taught exclusively on the basis of Galen’s text until the 14th century. Medical texts from medieval Europe are notably disinterested in the observation of human anatomy and inclined to repeat mindlessly the prototypes established in Galen’s text, accompanied by illustrations of the Roman scholar himself. [3] (Here, is an excellent LINK about 10 Bizarre Medieval Medical Practices)

We do not find any authentic anatomical illustration depicting diseases until the Renaissance, when both medicine and art had a glorious rebirth.

– Maingot

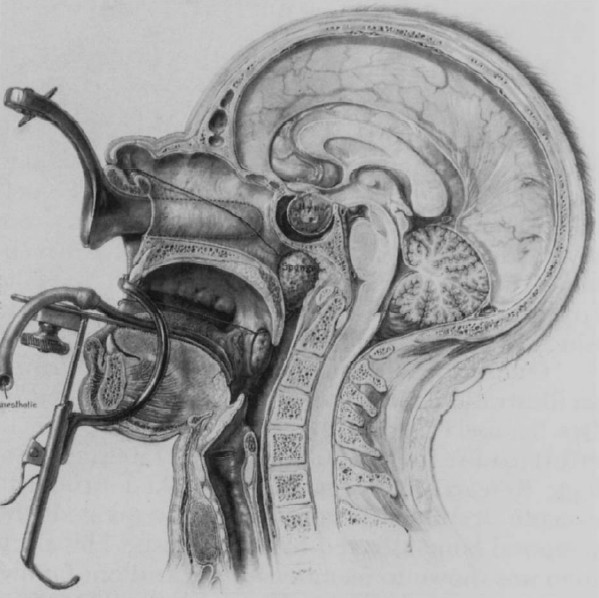

The Great Renaissance: The artists of 15th-century Europe began to reject the authority of Galen and rediscover the classical traditions of Greek art, as evidenced by the works of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Michelangelo (1475–1564), and Raphael (1483–1520), who performed dissections to study the human anatomy and created milestones in the history of art as well as medicine. During this period, art in general was a mixture of realism and idealism, and medical illustration was no exception. But it is important to note that they were interested in the study of proportion for artistic ends rather than in anatomy for its own sake. Nevertheless, Leonardo was able to combine techniques familiar to him from architecture and engineering in order to represent the human body as recognizable, ‘three-dimensional’ figures. The physician or anatomist of this period had a titanic job on his hands: find an accomplished artist who would undertake to work on cadavers. One must remember that there were no preservatives used, and it was, therefore, a mammoth task on the part of the dissector to convince an artist to devote time to the anatomical material.

It is Leonardo da Vinci, who is still considered the most influential artist in terms of the development of medical illustration, but Andries van Wezel (commonly known as Andreas Vesalius, 1514–1564), the physician of the Duchy of Brabant, did the most notable work in the history of human anatomy, thus paving the way for medical illustration, although probably Leonardo’s groundbreaking visual works cleared the way. His revolutionary work De humani corporis fabrica (‘On the Fabric of the Human Body’, 7 volumes, 1543) was the first complete and systematic description of the human body produced in modern Europe. It is the first true atlas of human anatomy. Vesalius stated that the 670 pages of text were secondary to the 186 visual plates, created by the illustrators of that period, which were accurate in their reflection and aesthetically outstanding. It was Vesalius who first realized that if certain artistic holdings were skillfully discarded, greater scientific value could be achieved in the illustrations. In Vesalius’ work, we discovered the economy of method and composition, ideally adapted to the field.

Post-Renaissance: The great post-Renaissance advancement was made possible by lithography. The German, French, and English texts of this period are attractive stuff to understand the progression. Many of the illustrations are not very attractively illustrated but are painstakingly done. An in-depth examination of these plates in some of these books cannot help but leave the onlooker with great respect for the illustrator. The introduction of printers was also a major influence on the advancement of medical illustrations. The trio (physician, illustrator, and printer) was attempting to get medical education into higher-quality books for medical students.

The most notable name in this period was Max Brödel (1870–1941), a German illustrator, stands as the father of modern medical illustrations. In the late 1890s, he was brought to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore to illustrate for Harvey Cushing, William Halsted, Howard Kelly, and other notable clinicians. His half-tone drawings had the authenticity of a photograph, and his pen drawings no longer looked like etchings. He also created new techniques, like carbon dust, that were especially suitable to his subject matter and resolved many printer-publisher practical problems. In 1911, he founded the academic department of medical illustration situated in the John Hopkins School of Medicine (now known as John Hopkins Medicine), still regarded as Brödel-Hopkins School. (For more information about Max Brödel, visit this LINK).

Indian scenario:

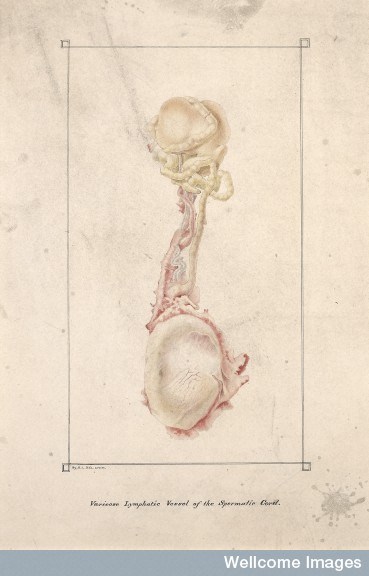

Both the visual arts and medical fraternities in India probably never showed any interest in this field. In my past several years of exploration in the field of medical and scientific photography and illustration, I did not find any medical illustrations that contributed to the field of medicine, except for one forgotten artist from India. Wellcome Images, one of the world’s richest collections of medical and social history, acquired a couple of watercolor paintings by Behari Lal Dasaround 1906 in Calcutta. There is no further information available anywhere about (probably) India’s first medical illustrator.

6 Apr 1906 By Das, Behari Lal, St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archives & Museum

End Note:

Today, in abroad, the aspiring illustrators complete a three-year course of study, much of it tied in with the medical course. No longer is the physician grateful to a landscape painter for illustrating the unfamiliar subject of viscera or restricting him to the microscopic detail of some strange bit of tissue. Just as physicians specialize, so have many illustrators, notably Brodel for gynecology, William P. Didusch (1895–1981) for urology, and Schlossberg for the heart. Today, authors in the western world can obtain illustrations prepared by a professional illustrator who has obtained training from the heirs of the Brödel-Hopkins school. The horizons of medical illustration, including all forms of medical communication, are wide and fascinating, which literally opened up a new dimension of biocommunication, research, and documentation.

Modern medical and scientific photography and imaging make a hard job much easier and take much less time. However, you can’t ignore the importance of illustration in medical science, especially when it comes to biomedical communication.

[1] Ollerenshaw R. Medical Illustration (The Impact of Photography on Its History); Journal of Biological Photographic Association, 1968; 36/1: 3

[2] History of science in classical antiquity: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_science_in_classical_antiquity

[3] Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 1986, Vol. 9, No. 2 : Pages 44-49